What's on the "Venus" of Willendorf's Head?

and what can she tell us about ancient gender roles?

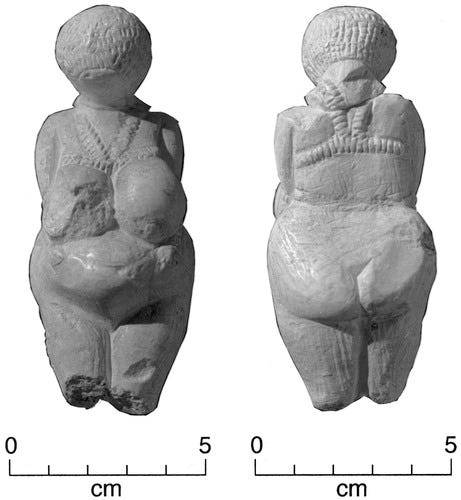

She’s an Upper Paleolithic Icon. Even if you don’t know her name, you probably recognize her curves. She is a small figurine (11 cm) found in Austria, carved from imported limestone around 30,000 years ago. I actually described some other well known European “Venuses” in my first Archaeolog. This type of figurine is one of our first glimpses into ancient art and ancient concepts of gender and sexuality. However, calling these types of figurines “Venuses” is anachronistic and perhaps misleading. We do not know whether this sculpture represents a goddess, an ideal, or what function it served. Some archaeologists have even argued that she may have been paleo-porn, which I hope is too ridiculous to be true.

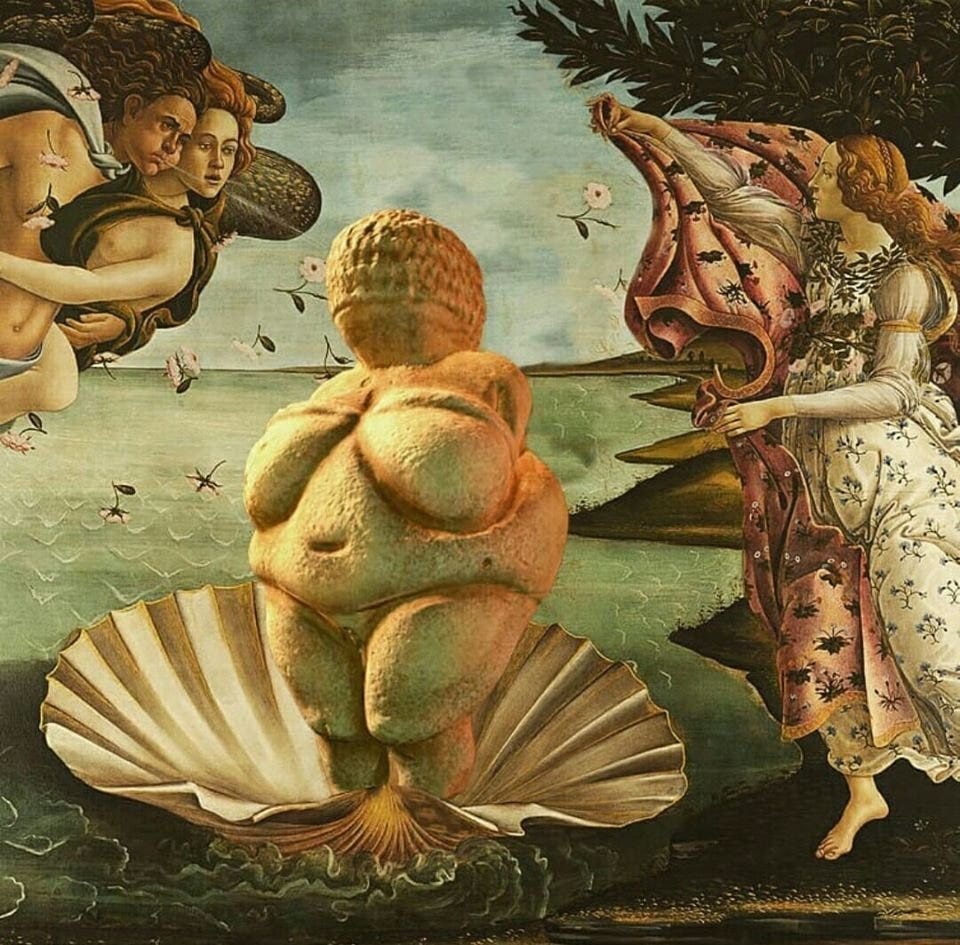

I often see versions of the Woman from Willendorf in contemporary art and design— Willendorf candles, tattoos, and wall art. I have the version candle right now and used to have a lovely painting of small curvaceous bodies all inspired by Willendorf and her colleagues. To many people interested in feminism, art, and ancient history, the veneration of this figurine seems to represent an illusory matriarchy lost to time. Her body, which probably represented some sort of ancient ideal, also works against modern standards of thin, waif-ish beauty. Rather than viewing curves as something to conceal or shed, Willendorf reminds us of the generative power of the female body— full breasts and bellies representing fertility.

But that just goes to show how interpretations of the past are mired in our own present politics. I reject interpretations that assert a modern male-gaze into the Paleolithic, because personally, I don’t want the male gaze to go there. The annoying reality of interpreting ancient art is that we will never know, for sure, what something symbolizes culturally. Think about how gestures, colors, and customs vary so widely today that something normal in your hometown may be offensive in another country. Now imagine how were supposed to interpret what iconography symbolized for cultures separated from us not only by distance, but by time. As I said, we are interpreters, and the best we can do is theorize. Some hypotheses have more supporting evidence than others!

So, who is the Woman of Willendorf? Is she a Venus? Why does she look the way she does, with small arms encircling her breasts and a completely covered face?

I just finished reading a lovely book called The Invisible Sex, written by three renowned archaeologists, bringing their unique specialities and skills together. As the title may suggest, the book explores human history from Australopithecus to modern Homo sapiens, considering the roles females/women played in our human story. J. M. Adovasio attracted me to the book because I am a fan of his analysis of archaeological basketry and woven materials, and also his feminist approach to interpreting the archaeological record.

Before I write a whole blurb on the book, I wanted to write this brief post about the Woman of Willendorf, because The Invisible Sex introduced me to a new hypothesis I had never heard before. Her stylized head has been interpreted as abstracted hair or some sort of face covering, but Adovasio and Soffer offer a different interpretation that I find compelling.

J.M. Adovasio is an expert on woven materials and perishable technology. If you are familiar with baskets, you may notice the similarity between the Woman’s spiraling textured head and coiled basketry. This would make sense, since the earliest evidence for weaving dates to this time period (30-20,000 years ago). In a 2000 article from the University of Chicago Press, Adovasio argues that her head actually represents a woven cap. The carving carefully details the radial pattern of the weave and the knotted center where the coiling starts. Adovasio notes that the warp and weft are visible on the cap as it winds from right to left. Clearly, the artist had a good understanding of coil weaving, and it was important to render it in detail. Could the Woman of Willendorf symbolize a master weaver, or perhaps function as a guide for someone starting a coiled basket? The similarity is striking, and with such attention to detail, I think this may be the best guess at what that Paleolithic artist was trying to capture.

In the article, Adovasio describes examples of other woven clothing such as snoods, bandeus, belts, and jewelry. It is hard to know whether or not they represent everyday wear or ritual garb, but the authors prefer the latter. The working assumption is that one does not carve art out of imported or valuable material just to represent an everyday person in everyday clothes. Though we cannot know for sure the social and cultural implications of the Venus figurines and their makers, the creation of such portable art suggests that these woman belonged to some sort of social group. Whether they are elites, religious leaders, eligible for marriage, master basket weavers, we cannot say for sure.

“The unambiguous assignment of particular technologies to any particular social grouping of individuals is a difficult endeavor in archaeology” (Soffer, Adovasio, and Hyland. 2000)

This quote above takes us back to gender. Do the Venus figurines represent humankind’s first socially constructed women, rather than females? What can we infer about prehistoric womanhood based on these figurines?

Adovasio, Soffer, and Hyland argue that fiber technology was likely women’s work and the Venus phenomena may represent an intensification of women’s labor during the time period in Europe. Furthermore, these figurines may speak to the value of women’s labor in the Paleolithic. Think about how essential clothing would have been for our hunter-gathering ancestors 30,000 years ago. “The String Revolution” as coined by Elizabeth Wayland Barber, allowed us to travel across continents, seas, and climates, and adapt to new environments. Perhaps the Venus figurines represent the important role women played as weavers— not only creators of life, but protectors of life through sewn hides, woven sandals, mats for sleeping, and woven roofs for shelter.

My biggest takeaway from The Invisible Sex, was not that our understanding of history needs to be completely re-written. It just needs to be re-gendered, somewhat. Both men and women played essential roles in creating culture, procuring food, and preserving our species. Third gender and other gender identities have also existed in ancient history, and are not a unique phenomena of our modern world (but that’s a topic for another article)! The issue with our interpretation of the past is that since women’s work has been undervalued in the present, so has women’s work been undervalued in the archaeological record.

Men are often written in to archaeological interpretations while women are written out. Often, interpretations add gender where gender cannot be interpreted at all— such as stone tool making or cave art. There are plenty of examples, outlined in Invisible Sex, where the makers of artifacts, the creators of history, are presumed male based on gender bias alone.

Though there is evidence that women were likely the master weavers of the Paleolithic, that does not mean their work was not valuable. I often want to find examples of women doing historically male stuff, like hunting, to prove sexism wrong. Really, we should be pulling modern gender issues out of interpretations and working with the evidence we have. Furthermore, we need to value women’s work throughout history and prehistory, just as we need to recognize the value of domestic labor today.

Invisible Sex and new interpretations of the Venus of Willendorf has really got my feminist archaeology brain working, and I still have much to learn and say about the topic of women’s roles in the deep past. I hope you enjoyed reading this brief exploration into gender roles via the Venus of Willendorf— perhaps your interpretations of ancient history have changes like mine have!

To further support my work: buy me a coffee! <3

References:

Soffer, Olga, James M. Adovasio, and David C. Hyland. "The “Venus” figurines: textiles, basketry, gender, and status in the Upper Paleolithic." Current Anthropology 41, no. 4 (2000): 511-537.

This is the first time I’ve seen a photo of the top of her head and yes, it definitely brings to mind a coiled basket. I’ve woven baskets, including coiled ones, and the center starting point shown is identical and unlike braids.

Something about them doesn’t strike me as fertility objects. One would expect the pregnant belly to be preeminent, not the other curves. Was the typical woman of that era so well fed? Or just the opposite? Was Venus perhaps symbolic of abundant harvests?

If the “hair” or hat is woven, would we conclude that women or girls carved these? Why not? Have others always assumed men did the carving? Why?

Commenting so that I see more posts about historical fashion/textile history. I hope you're able to continue dismantling your bias that women being important means women doing male roles. How can a community live without food, clothes, medicine & child-rearing? This is what makes us powerful! Without women spinning & weaving we would not have a massive sails that made ancient sea-fairing & trade possible. Without women we would not have the invention of the electric weaving loom.

I really recommend reading The Fabric of Civilization- Virgina Postrel.

It talks about the history of textiles and how they've shaped our world from paleoithic to how textiles may carry us into the future.