Late the other night I went on a wikipedia rabbit hole of prehistoric art prompted by some reels by one of my favorite internet archaeologists— Miniminuteman. I have been obsessing over his series on Ancient Apocalypse where he does a great job debunking Hancock’s theories and making archaeology accessible, entertaining, and accurate!

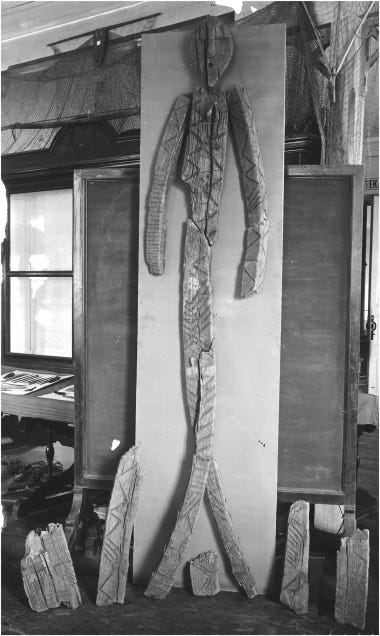

Entry 1: The Shigir Idol

When I saw the Shigir Idol for the first time, I gasped. It is rare to see artifacts this ancient made from organic materials like wood— which is why our understanding of past cultures are biased by preservation. When we think of the Late Pleistocene and the early Mesolithic, we think entirely in stone, but this paints a dull picture compared to what the world would have looked like for hunter-gatherers at this time. The Shigir Idol is a peak into this artistic world. Bogs are our one saving grace, since they preserve organic remains in their acidic, anaerobic environments (think, bog bodies, bog clothes, bog BUTTER)! The Shigir Idol was found in the Shigir peat bog (in the Middle Ural region of Russia) in 1890. It’s a testament to the visual and artistic language of the Late Glacial/Early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. I wonder if the 2.8 meter high figure was actually positioned by the bog as a guardian or a warning…

Originally, the wood was radio carbon-dated to around 9,500 years ago, however recent dating techniques have pushed that back even further to 12,000 years ago.

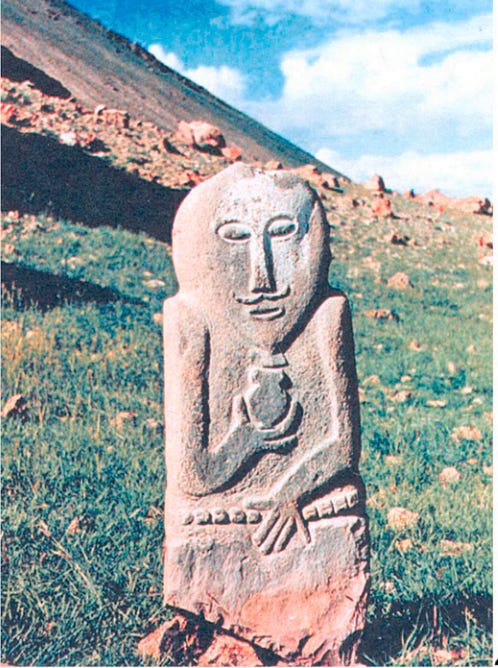

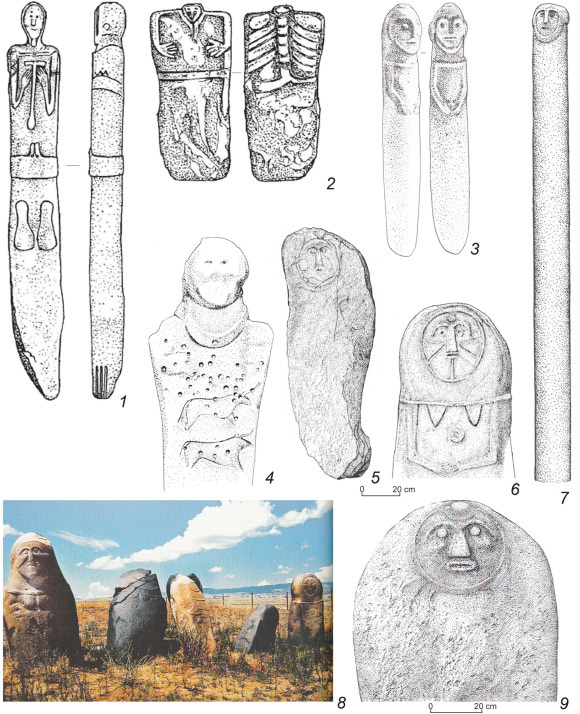

Entry 2: Anthropomorphic Sculpture in Eurasia

The Shigir Idol got me looking into Russia and Eurasian Steppe. I know basically nothing about the archaeology of this region and was a bit blown away by the stone sculptures from Yamnaya and other cultures. The paper I read discussed how stone sculptures could be a continuation of an earlier wooden sculpture tradition that was lost. I also just think they are really cute…

These statues probably served as a sort of grave marker or cenotaph— which is a monument to honor the dead not associated with remains. Cenotaphs are also common monuments for those who died in war and remains are lost.

Some of these are also called “balbals”— which is a Turkic word for ancestor or grandfather.

I just did a brief jump into this subject and perused wikipedia, but I am excited to learn more about them. This lead me towards Scythian Deer Stones and burials, which I think I will investigate for Log #2

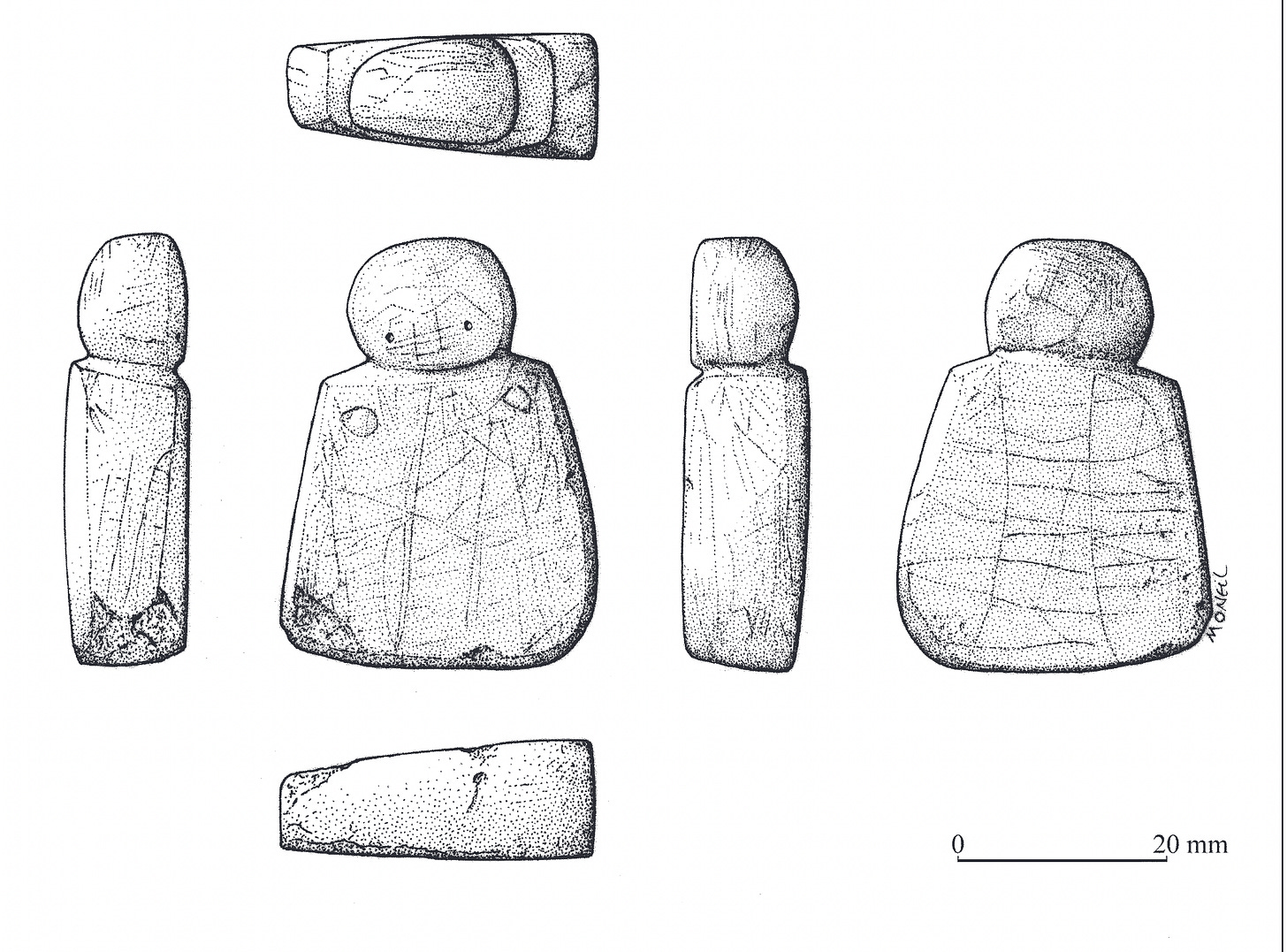

Entry 3: The Westray Wife

The Westray Wife is actually the oldest depiction of a face in the UK, and the midden she was found in has been dated to around 2600 BCE. I do love how they call her a “wife” just for alliteration I think. I love the whole venus thing because we have numerous examples of handheld female statues from the Paleolithic, but some of them are so stylistically unique. The Westray Wife (which is from the Neolithic) is a simple blocky figure with a trapezoidal body and a round head decorated with etching. Her face seems to be smiling at the ground, a la, you don’t know you’re beautiful! Don’t you wish your man could carry you around like that? And show you off to his friends?

I wanted to include the Grimes Goddess as well (because she’s funny and cute). However, her authenticity has been questioned along with the other objects in the ritual assemblage (including a chalk phallus). In Chapter 14 of Visualizing the Neolithic, the author outlines how the lead archaeologist A. L. Armstrong from the Grimes Graves site really wanted to find a paleolithic deposit and his sculptor wife had made replicas of the Goddess and other objects. The author makes a compelling case, but it’s still a mystery.

Paleolithic venuses appear to be fertility figures emphasizing the breasts and round stomach of a women’s body, more like the Grimes Goddess. Referring to this class of figures as Venuses may not be the most accurate, but I guess it has a better ring to it than fertility figurines? Many of them lack faces (either by design or because the heads were lost). On the other end of the visual spectrum is the Venus of Monruz from ~11,000 ya—a small, sleek sculpture made of black jet that reminds me of a Brancusi (she was discovered post-Brancussy but he would have loved her). The material and the abstracted curves feel so modern, and I do wonder if she truly is a venus or something else entirely, but there is no denying her curves (lol)!

Entry 4: Bison Cave and Archaeology of Darkness

This summer I read The Archaeology of Darkness edited by the Irish cave archaeologist and ATU professor Dr. Marion Dowd (she actually taught a field school I attended and is truly amazing!).

This book changed the way I think about cave art— specifically how we experience cave art today. When you visit the Lascaux replica, it is completely lit so you can see everything in detail, which is a far cry from how the artists would have experienced the cave 17,000 years ago. One element I loved about my visit to Newgrange in Ireland this summer was when they turned off the lights, and slowly you are entirely consumed by darkness. Rarely in our modern life do we experience the visceral intensity of darkness. The book explores the spiritual significance of caves as inaccessible, arduous, existential, places— and perhaps caves as portals to the “other world”.

Chapter 2 (Darkness Visible. Shadows, art and the ritual experience of caves in Upper Paleolithic Europe) discusses the “dialogue” between a person and the cave as they explore the space with a limited light source. Art was never viewed comprehensively and the shape of cave walls were used to emphasize the shape of animals and figures. Walking through a cave with a torchlight would create a visual experience of art emerging from the darkness, moving in motion with flickering light and the shape of the walls.

The Bison man shadow in El Castillo Cave illustrates this perfectly. When this chamber is lit, a stalagmite (decorated with a painted bison) casts the shadow of an anthropomorphized Bison figure. Shadows would also have played a major role in cave art, speaking to the importance of darkness in interpreting these spaces.

An episode on Lascaux from The Ancients podcasts also discusses the role of sound in viewing cave art. The echoes of stomping feet would create a stampede audio-affect. I never realized how cave art would stimulate multiple senses, inspiring fear, awe, and wonder. Now I know if I ever do get to visit a paleolithic cave, I should make sure to see it the old fashioned way.

What I’ve been consuming:

Digging Up the Past by Leonard Woolley— it’s a good look into the history of classical archaeology and how the old school guys in the early 20th century used to think. Wooley outlines the archaeological process and how he leaves most of the excavating to skilled local laborers… it is chock full of elitism and racism, but I think it is valuable to learn about the history of archaeological practice and how echoes of these sentiments still exist in the field.

Zora Neale Hurston’s ethnographies, specifically the story of Cudjo, one of the last African slaves in America. Her observations in the Sanctified Church are also extremely interesting and challenge dominating ethnographic practices at the time. She recorded voices that would have otherwise been lost.

Visualising the Neolithic, which I want to read now after writing my entry on the Westray Wife <3

Citations:

Shigir Idol:

Terberger, T., Zhilin, M., & Savchenko, S. (2021). The Shigir idol in the context of early art in Eurasia. Quaternary International, 573, 14-29.

Anthropomorphic Turkic Statues:

Bobrov, V. (2021). Shigir idol: Origin of monumental sculpture and ideas about the ways of preservation of the representational tradition. Quaternary international, 573, 38-48.

and wikipedia.. opps!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_stelae

Westray Wife and Grimes Goddess:

Varndell, G. (2012). The Grimes Graves goddess: an inscrutable smile. In Visualising the Neolithic: Abstraction, Figuration, Performance, Representation. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers (Vol. 13, pp. 215-225).

Venus of Monruz…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_of_Monruz

Bison Cave:

Pettitt, P. (2016). Darkness visible.: Shadows, art and the ritual experience of caves in Upper Palaeolithic Europe. In M. Dowd & R. Hensey (Eds.), The Archaeology of Darkness (pp. 11–24). Oxbow Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dng1.9

https://shows.acast.com/the-ancients/episodes/lascaux-cave-ice-age-art

Visualising the Neolithic:

Cochrane, A., & Jones, A. M. (Eds.). (2012). Visualising the Neolithic (Vol. 13). Oxbow Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dwd6

Loved reading this post. I’ve never come across the Shigir Idol before and it blew me away too!