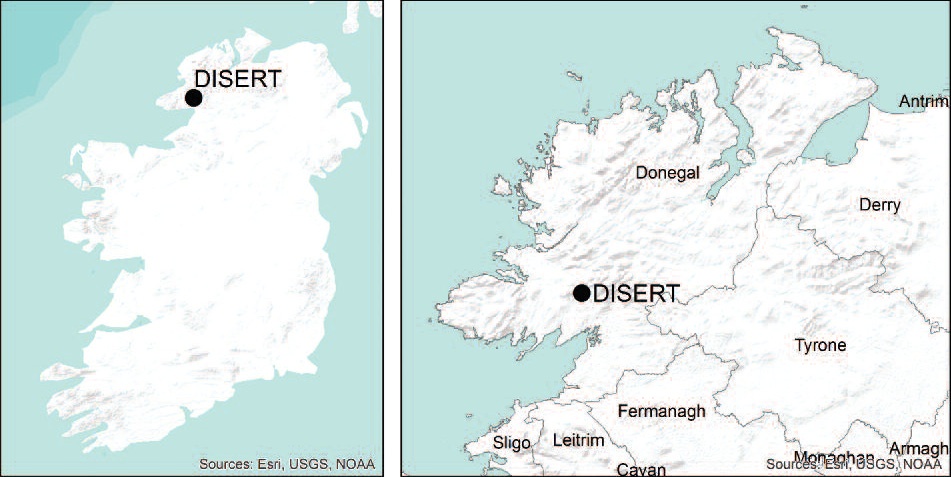

For the past couple weeks I’ve been on an excavation in County Donegal, Ireland, at the secluded monastic site known as Disert (https://disertheritage.com/ ). This field season was a surprise encore after three prior seasons led by archaeologists Dr. Fiona Beglane and Dr. Marion Dowd of Atlantic Technological University Sligo, supported by a team of students and volunteers.

(Flexible Learning Courses in Archaeology | ATU - Atlantic Technological University)

I was incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to attend this field school— coming all the way from my grad school in LA to work on both the excavation and post-excavation process. In 2018, before I had even decided to focus on archaeology in college, I attended another field school in Ireland at the Iron Age royal site of Dun Ailinne (or Knockaulin). I spent a month living with a host family in a small town, working head first in a trench on top of a hill with panoramic views of the green farmlands, the Curragh, and Old Kilcullen. It left a lasting impression on me and changed the trajectory of my life. I knew I loved history, nature, working with my hands, and using my imagination to speculate how people may have lived thousands of years ago. After pivoting a couple of times post-pandemic, I found myself right back where I started— hiking lush hills spotted with thistles and grazing sheep to dig, trowel, sieve, measure, and draw everything about dirt (and lots and lots of rocks).

The name Disert has many meanings: a desert, a hermitage, or a place apart. The name captures the secluded nature of the early medieval settlement where only a handful of incredibly pious (or troublesome?) monks would have lived. Situated along the Eany Beg River just south west of the Bluestack Mountains, the site offers spectacular views of the surrounding landscape, but is prone to temperamental winds and rain which we experienced daily on site. (Though the rain was much preferable to the swarming midges, who only came out in good weather and are best described as gnats that are hungry for blood).

It is said that one of the patron saints of Ireland, Saint Colmcille (or Columba), came to Disert in the 5th century AD. He looked through the central hole of a quern stone that sat on the altar and blessed everything that he could see, speaking to the lush fertility of the land and how the environs of Disert contribute to its spiritual value.

****We talk a lot about enclosures at Disert, and I did not really know what that meant prior to arriving in Ireland. Basically, the site is encircled by a dry-stone wall that is intact at some points and buried or absent at others. Early medieval monastic sites typically had multiple concentric circular enclosures with its most sacred area, usually the church, at its center. There is also an enclosure around the graveyard and cillin (graveyard for unbaptized children). The arch enclosure is a bit of an anomaly, since it emerges from the southeast portion of the ecclesiastical enclosure like an awkward addition to a house. Oasis in the Desert has great aerial photos of the site and its features. ****

The unique role of Disert from early medieval times to today…

Archaeological sites serve as physical and visual reminders of the past, like illustrations to a story or a textbook emerging from the landscape. Some of the most meaningful historic places are the ones where the story continues to unfold in the present day. Disert is one of these places where the tradition of pilgrimage or turas lives on. Everyday, locals and tourists alike came to visit the site and see what us archaeologists were up to. A local historian Helen Meehan has contributed an immense amount of knowledge and research on the site and its parish (Inver Parish by Helen Meehan). In the early medieval period, it was a monastic hermitage blessed by St. Colmcile. Then, during the Penal Times it was a sanctuary for persecuted Irish Catholics and a community graveyard. Until the mid-20th century, it was a cillin, or a graveyard for unbaptized infants and locals still remember family members buried there. The altar, graveyard, and holy well serve as spiritual places for visitors to this day, and we had the chance to attend rosary at Disert on St. Colmcille’s feast day. I don’t think I’ve heard Hail Mary prayed so effortless and expeditiously in my life, and I was surprised to hear that actually it was a slow down from previous years.

The icon of Disert is the arch situated at the south east of the ecclesiastical enclosure (pictured above). Hikers and tourists come to see the arch, where it’s said that if you crouch through it three times and lay on a stone slab your backache will be cured.

Mica-schist and quartz stones are brought by visitors/pilgrims and placed on the lintel of the arch. At the end of our excavation, we placed a variety of rounded cobbles, quartz, and flowers there as well.

The arch itself is the product of a glacial erratic stone (or a large boulder) that was deposited by the glacier that entombed Ireland during the Ice Age (Late Pleistocene). Weathering caused the large boulder to crack in half creating the two upright stones of the arch. A lintel was added at some point, though there is no way of knowing when (Organic matter is necessary for carbon dating, which is why charcoal, bones, and shell are so valuable to archaeologists (Some rocks can actually be dated using other methods but that is not applicable here)).

There are other glacial erratics in the landscape that probably influenced the construction of the ecclesiastical enclosure, like how they inspired the creation of the arch itself. I imagine the monks envisioned the hermitage and altars in the large boulders haphazardly plopped on the hillsides before constructing the settlement at Disert.

The excavation process:

At the beginning of the brief field season we were divided into three teams— one for each trench. Every morning, we would hike up with our gear (shovels, buckets, dumpy level, grids, planning boards, etc., always forgetting a plumb bob), set up our tent for the inevitable rain, and get digging. I mentioned stratigraphy before, which is basically how we record soil change as we excavate deeper into our trenches. European archaeology defines each layer as its own context which needs to be properly recorded (context sheets include the dimensions for a context, soil description, associated finds, and its relationship to other contexts). While my team’s trench had 14 contexts, some of the other trenches had almost 30 (which got very complicated during the post-excavation process)! I was stunned with the ease at which our site director could identify changing soil and see colors I didn’t know existed.

Again, since archaeology is a destructive process, we must go slow to record everything properly. We’re not necessarily dusting dirt with brushes, but we are carefully skimming the soil with our trowels so we don’t destroy a surprise artifact, or dare I say, a burial. (Research excavations like ours tend to avoid burials—even though there are known graves at the site, that would be the last place we’d want to excavate out of respect for the dead and the community. If we did stumble across human remains, we would have to halt our work and call in the specialists).

The whole excavation process is slow, methodical, and in a lot of ways, meditative, which is why I enjoy it so much.

My team’s trench was not too complicated. A ditch had been dug inside the ecclesiastical enclosure, and the natural soil had been thrown up beside it to create a bank. The ditch was then filled in with layer after layer of stones and grey clay that I had the pleasure of recording in detail, to scale. Once the team caught on I was half-decent at plan and section drawing, I found myself poring over the planning board for almost the whole second week of work. Now I have the southwest enclosure wall engrained in my memory and I feel triggered every time I see stone architecture.

So, what did you find?

Our bus drivers and folks we met at the pubs would often ask us, what are you finding at Disert? Any bronze swords? Gold lunulae? Ancient tombs?

In reality, the artifacts we were finding were not all that “exciting”, but we were excited nonetheless by our progress. There is a pervasive stereotype that archaeologists are treasure hunters, or worse, grave robbers (due to the history of the field and portrayal in the media, this stereotype is a reasonable one). But, the National Monument Service of Ireland, and most governments for that matter, do not grant excavation licenses just to find treasure—there needs to be a research question justifying the work. At the end of the day, archaeology is a destructive process. Once sites are dug up they are permanently altered, which means that excavations need to balance research and data collection with preservation. We are not just digging holes willy-nilly.

The goal of this year’s excavation was to address the mystery of Disert’s arch. Was it really a megalithic structure that pre-dated the monastic settlement or is it a later component of medieval or even post-medieval religious ritual at the site? Our big finds were large chunks of charcoal that can be carbon dated, and will therefore help us better understand the arch enclosure. Charcoal may not seem glamorous, but it is incredibly valuable for interpreting the site!

Ultimately, the work is not about what “treasures” we find, but how well we are able to answer the excavation’s underlying research question.

In conclusion,

I think I learned the hard truth about my field this summer— which is that research questions only brings about more questions, and we will always want one more week, one more month, one more field season. We will never know everything, which is the beautiful, irksome, and poetic curse of archaeology.

Unfortunately, this was the last field season for Disert, and it was already an unexpected one at that. To think we may have never known for sure the significance of the arch or when it was built! As post-excavation continues and our samples get sent out to specialists, we will hopefully have more answers, and inevitably more questions, that could be addressed by the archaeologists of the future…

Thank you for reading if you did, I tried to make it is a brief as possible if you can believe it.

<3