I ended up taking a bit longer to write this than expected… oh well! Started data collection for my thesis which is very exciting and a bit time consuming…

We’ve all been busy and stressed I bet, so here are some new entries to my “archaeo-log” to inspire/distract you. Looking at the past always helps me put things in perspective <3.

Entry 1: Minoan Purple (aka Tyrian Purple)

Since my childhood, I have been fascinated with the mysterious Minotaur inspiring civilization, the Minoans. This name actually comes from King Minos of Greek myth since the true endonym (how the Minoan’s would have called themselves) is unknown. The palaces, art, and myths left behind on the island of Crete are truly impressive, as well as their rigorous bureaucracy recorded in Linear A and B (which I have tattooed on my wrist).

I couldn’t help clicking on a nearly 20-year old Odyssey Documentary on the Minoans, reuploaded to youtube, to entertain me during some monotonous lab work.

In the Odyssey episode, we are led around Crete by the historian Bettany Hughes, who goes diving herself for some “charmless” murex snails.

Since I work in a Coastal Archaeology lab, I have a concerted interest in marine gastropods and their uses by archaeological cultures. I was fascinated to learn that these murexes were actually a source of highly valuable purple dye and would have been a key export from Crete to the rest of the Mediterranean world. In the Odyssey, Homer refers to this dye as haliporphyros, or sea-purple (Steiglitz 1994, 46).

This dye is known as Tyrian purple, since it was believed to be produced in Tyre, Lebanon. Archaeological evidence now shows that the Minoans were producing this dye around the 20th-18th century BC, centuries before Tyre (Steiglitz 1994).

Each shell would only produce a few drops each of valuable mucus, which means hundreds of thousands of pounds of shells were required to make the dye. The laborious procurement and processing of the shells contributed to its high cost and led to the creation cheaper imitation dyes. However, the real stuff was required for religious and royal purposes, as exemplified in the Rabbinic law that states Tyrian purple must be used for dying prayer shawls (Stieglitz 1994, 46).

Dr. Hughes in the Odyssey documentary shows us a perfectly drilled hole in one of the murex shells. These holes are animal, not human made, and are evidence of predation. These small, harmless looking critters are actually predators who use their pointed shells to drill into other gastropods. Archaeologically, these drill holes indicate murex farming/production, where the snails were kept in close-quarters and ended up cannibalizing one another! Farming these snails was probably much more efficient than diving.

Tyrian purple remains an expensive and prized pigment to this day, and perhaps we should call it Minoan instead?

Entry 2: Skara Brae (Neolithic Scottish Dwellings)

Skara Brae was a Neolithic settlement in Orkney, Scotland, covered under sand dunes for millenia until a storm unearthed the site in 1850. There were three phases of occupation between 3180 and 2500 BCE. Since the coast was a few kilometers west at the time, the settlers would have been herders and farmers growing wheat and barley. An isotopic study of sheep teeth found that they were primarily consuming seaweed (Balasse 2023)!

I can’t remember who told me about Skara Brae (perhaps one of my professors), but when I heard of stone-built Neolithic structures, I had to research further. Neolithic homes were often constructed out of wood, so hearing about stone dwellings was news to me (I know Irish prehistory better than the rest of that part of the world, so that’s my only perspective on the Neolithic).

When the first neolithic farmers/herders arrived in the knoll, there were no trees for constructing houses. Instead they built with stone and used whalebones and driftwood for roofing. They likely used driftwood and peat in their hearths. The first occupants also used the remains of a shell midden (piles of human food refuse) from previous hunter-gatherers to insulate stone walls.

The occupation phases at Skara Brae were punctuated by natural disasters. The first inhabitants, who left shell middens behind, fled the area after a flood in 3161 BCE. 75 years later, the next wave of inhabitants arrived and built the dwellings of Skara Brae. The end of Phase I correlates with the Bronze Age collapse, though it is not clear why the founders of Skara Brae left.

Another 70 years went by and the second phase began with new settlers building larger, semi-rectangular structures out of the previous circular ones. Again, a flood devastated the area and it was abandoned, but not before someone left an inscription telling of their plight.

1. Hail comes, a lot comes.

2. It comes again, hail rains anew.

3. Now the hut swims; in misery swims the family as well.

4. A drink will realize a lot of diseases.

5. All the dilapidated ewes were driven away into the mist.

6. Now the cattle and ewes run wild.

It’s a haunting inscription, and I wonder why it was left there at all. Was it a warning or just an expression of grief? It seems that the writer wanted to explain why they were leaving their once abundant home around 2665 BCE.

The third phase of occupation was a century later in 2550 BCE. These new inhabitants rebuilt the roofs and lived comfortably until the volcanic eruption of Hekla in 2345 BCE. This eruption originating in Iceland had far-reaching disastrous effects for North Western Europe (primarily Ireland, the UK, and Scandinavia). Winds carried toxic hydrogen fluorine gas which killed all livestock. A tsunami eventually buried Skara Brae until its rediscovery in 1850.

*All info from Harris 2021 and Balasse et al 2023*

Entry #3: New Nazca Lines!

I was excited to learn that 303 new Nazca lines were found from a paper published this year in PNAS. (All subsequent information is from this paper).

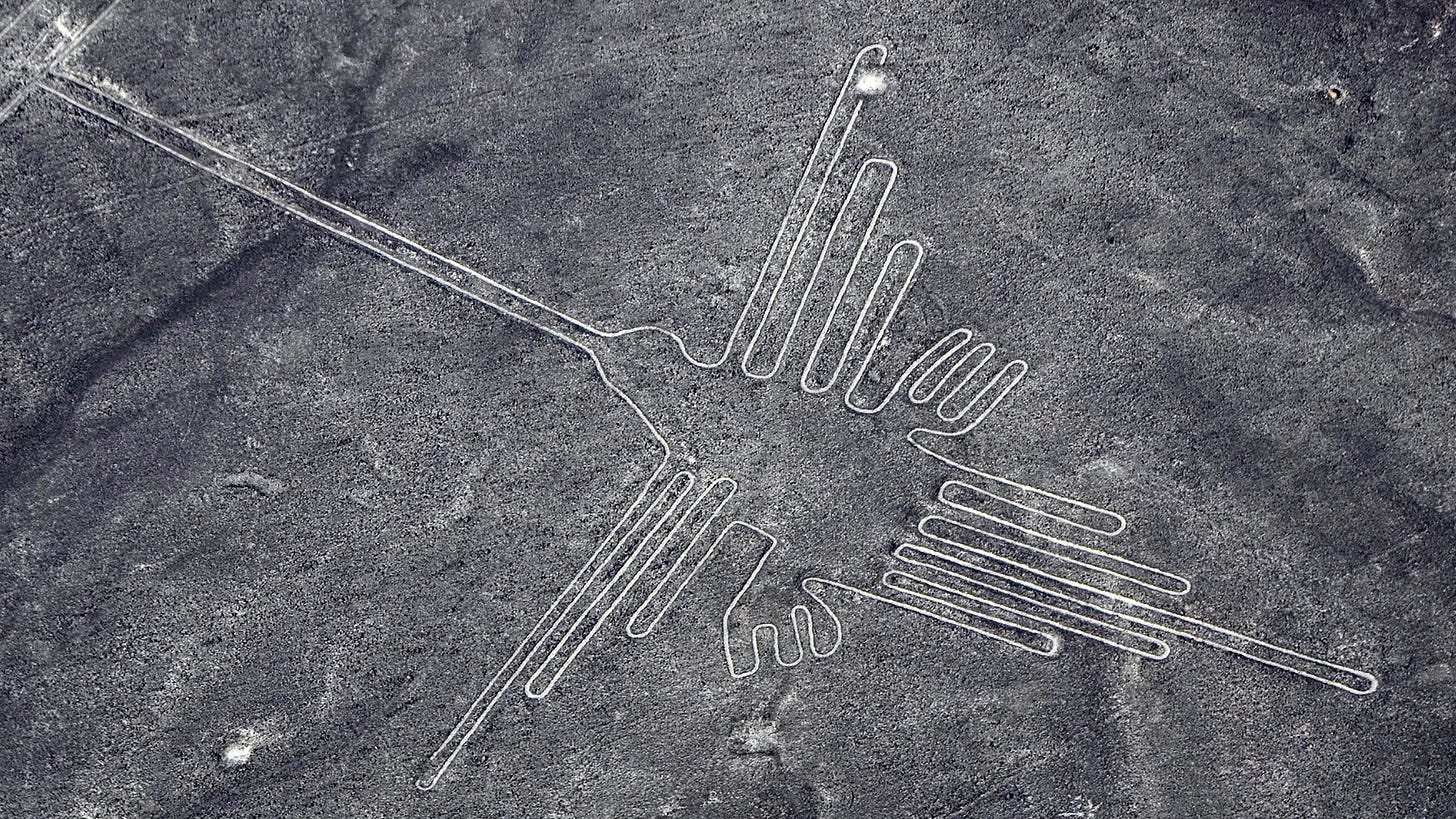

Nazca Pampa is a dry vast plateau where these geoglyphs have remained undisturbed for thousands of years. The large linear geoglyphs, such as the famous hummingbird shown below, were rediscovered in the early 20th century thanks to planes and aerial photography.

The geoglyphs were dated by association with pottery styles and iconography. The Initial Nasca Period dates from 100 BC-50 CE. Line-type geoglyphs seem to be later, Early Nasca Period (50-300 CE), while the relief-type are from the Initial Period or even earlier

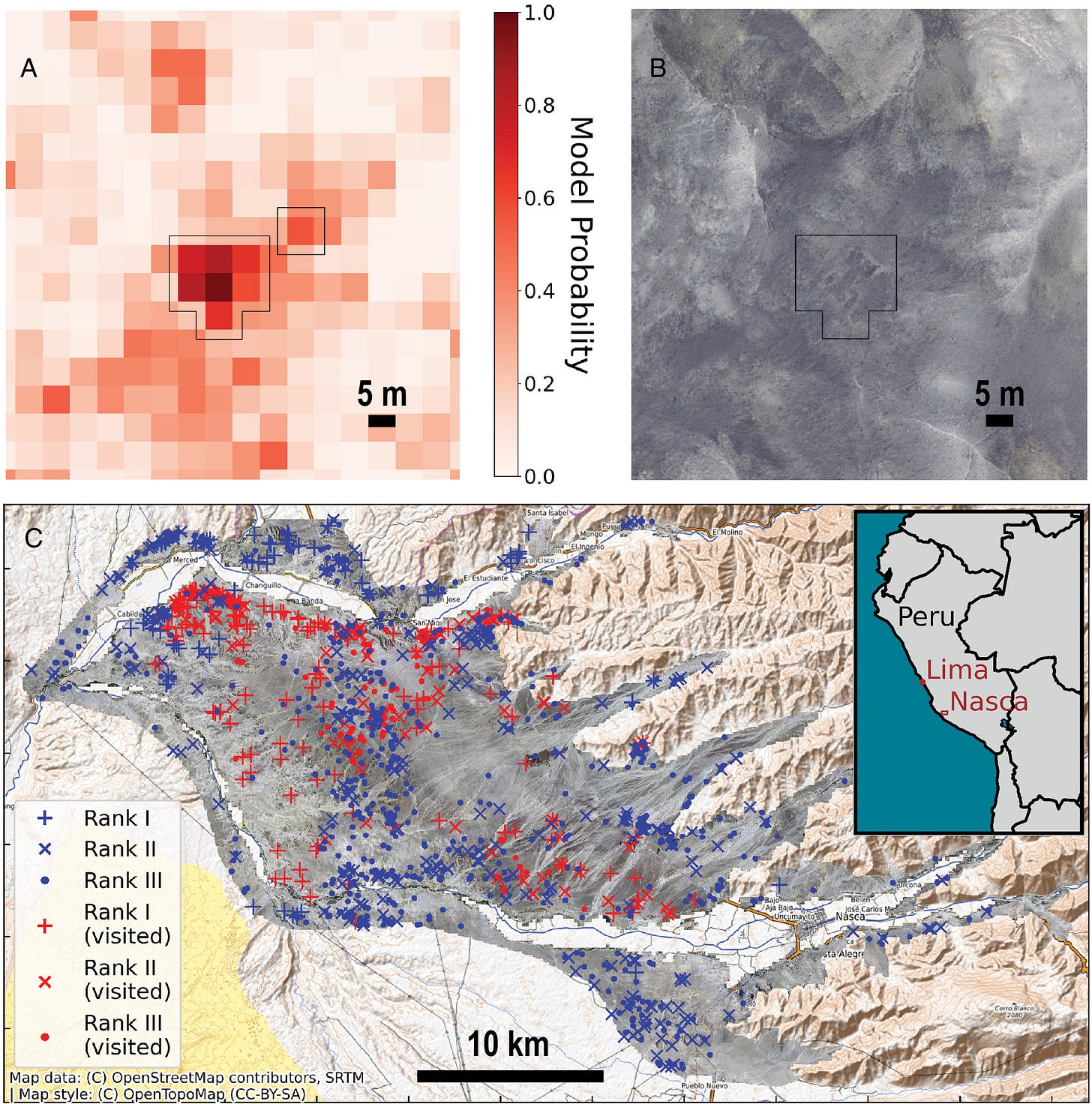

These new discoveries were made with the help of AI to identify relief-type glyphs which are difficult to see with the naked eye. This study is a great example of how AI technology can transform archaeological research. Around 400 lines have been located over the past century— however, 300 were found in 6 months alone with new tech, leading to knew insights and interpretations of these mysterious geoglyphs.

The geoglyphs are divided into to two categories based on construction: line-type and relief-type. Line-type, like the hummingbird, tend to be large scale depictions of wild animals created by moving gravel and drawing lines into the ground. Relief-type, the focus of this new research, are smaller and created by piling rocks and gravel into designs. With this new wealth of data, it seems like different forms of geoglyphs also had different styles and functions. While the famous, line-type geoglyphs depict birds, sea animals, monkeys, etc. the relief type show humanoid figures and domestic animals.

The AI software needed to be trained to identify the Nazca geoglyphs, however they only had a couple hundred images as opposed to a couple thousand typically used to train AI. Of course, the more images and examples they had to train with, the better the AI would be. To address this, researchers used natural photographs and specifically tailored the AI to recognize relief rather than line-type geoglyphs.

The AI tech didn’t independently identify geoglyphs, instead it ranked areas by likelihood. The highly probable images were then examined by archaeologists, who spent around 1,200 gleaning through the data to find new geoglyphs. I feel like mentioning this because AI cannot really replace human efforts, but it is a tremendous help. More time can be spent synthesizing and analyzing, rather than collecting data. Ultimately 178 of the 303 new geoglyphs were recommended by AI.

So, what was the function of the Nazca lines?

I remember learning on Ancient Aliens as a kid that they were for communicating with gods who were actually, of course, aliens.

Alien explanations are pretty dubious and tend to distort the real histories of these cultures and sacred places. The results of this study have revealed a compelling hypothesis that I think provides a more reasonable explanation for the relief-type geoglyphs.

These smaller symbols of humanoids and domesticated animals are actually visible from the nearby Nazca trails, as seen in the image below. Perhaps they were to communicate something to travelers or guide them on their journeys. This seems to be a strong example that the lines were for humans, and not extra-terrestrials, lol :)

Entry 4: Basket Weaving and Perishable Technology

Recently, I’ve been extremely interested in basket weaving and the art of Native California basketry. I am also really interested in how we assess the archaeological record for basket weaving since it is a perishable technology— meaning the organic plant material does not preserve well over time. Basket technology is interpreted through indirect evidence such as associated tools (awls), asphaltum pebbles, and impressions.

What sets weaving apart from other art forms is process. Weaving does not happen in a vacuum— it comes from generations of knowledge and land management. A huge issue for weavers today is access to materials since source areas are often on private or park land. Plants like juncus, rushes, willow, and sumac, many of which need wet environments to grow, have also been impacted by urbanization and land degradation.

Collecting materials happens at different times of the year, often with family or community. Resource areas are maintained and roots are even dug up and straightened to provide the best material for weaving. Once material is collected it must be processed by splitting, drying, or soaking, depending on the plant and weaving technique.

In this way, the process of making a basket is much different than putting paint on a canvas. It is a long-term process in which the same source areas are used by communities for generations.

If you are interested in learning more directly from indigenous weavers, watch this lovely PBS SoCal documentary on the subject!

As I explained earlier, woven materials tend to be made out of plants, and plants do not preserve well in the archaeological record. This means that our understanding of woven materials is generally lacking, and much of what we know in California is thanks to oral histories and the continuation of this art by weavers today.

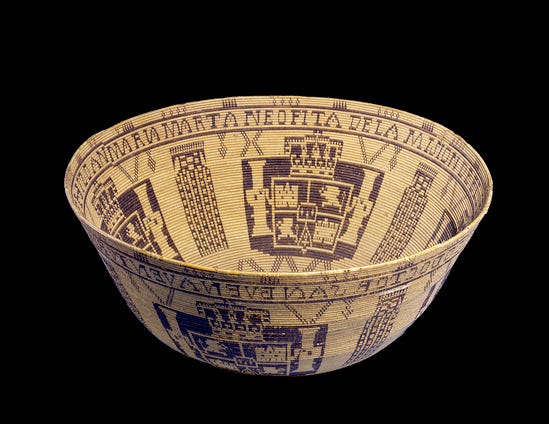

One of the oldest non-archaeological baskets was made by a Chumash woman at the Mission San Buenaventura. The name given to her by the missionaries, Maria Marta, is woven into the basket itself, making it the oldest basket with a known weaver. Her actual name was recorded as Laputimeu, and she was converted in the Mission at the age of 21 in 1788. The basket reads "Maria Marta, neophyte of the Mission of Seraphic Doctor Buenaventura, made me yr…” The rest is incomplete since the weaver ran out of room. The design replicating images from the Spanish peso are made with impressively fine weaves (320 weft strands per inch). The larger design is the Crown and Shield coat of arms, and the narrow designs represent the pillars of Hercules.

Basket weaving underwent functional and stylistic change during the Mission period. This was a time of hardship and loss, as Native Californians were forced to move off their land into Spanish Missions and to convert to Christianity. Thousands of Native Californians died during the Mission Period, so the context of the creation of many of the baskets we see today in museums is one of survival and strife. By the 1890s, native baskets had become a commodity and weavers made baskets to sell commercially.

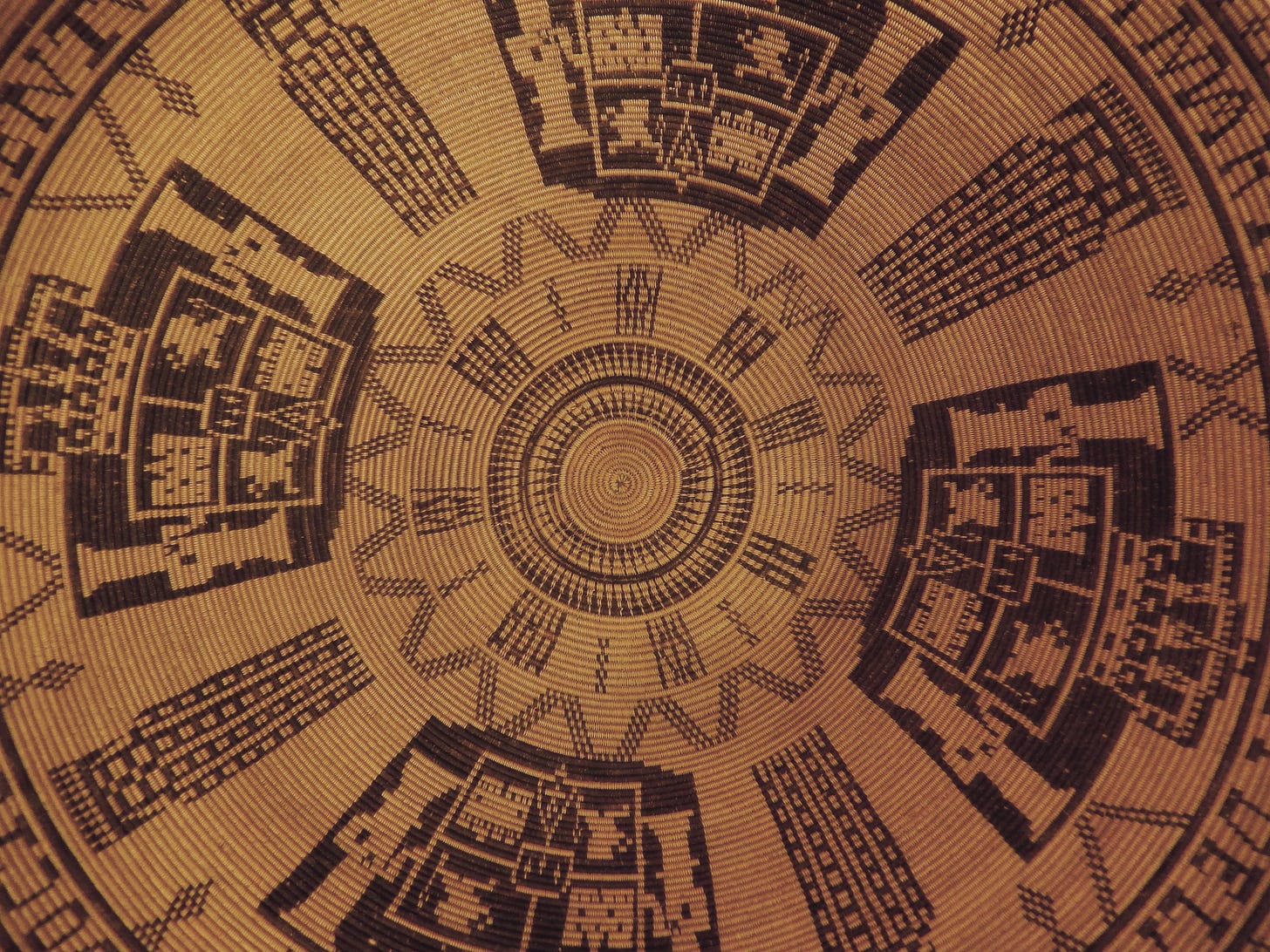

Another interesting feature of this basket is the incorporation of white feathers, which are hard to notice at first glance. This is extremely unique for Chumash basketry and perhaps was influenced by Pomo or Ohlone designs. Pomo baskets are known for their ornate use of colorful feathers and shells (example below). I will probably talk more about basket weaving in future articles because it is such a beautiful art form with a long-term generational process unique to the material.

I was going to discuss archaeological baskets, but I am running out of space, and perhaps should dedicate a whole article to the topic. For now, I’ll just link one of the largest Chumash baskets which was found in 2015 preserved in a cave in Los Padres National Forest. It would have been used for storage and dates to around 350-450 years ago, so 16th and 17th century.

Recommendations

I always write way more than I intend to, lol! But it is a good exercise in research and writing a bibliography in the AAA style.

But to wrap up, I want to share a neat book I just started called The Other Ancient Civilizations by Raven Todd DaSilva. It is geared to non-specialist readers and is very approachable and succinct. It is a nice break from scholarly articles while still learning about archaeological cultures.

For anthropologists or academics (or anyone interested!) I’d also recommend Global Transformations by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, the late Haitian anthropologists. It completely breaks down the concept of Western knowledge and how it only exists in opposition to the non-Western other. It should be an essential read for anthropologists and makes clear how deeply connected the Western tradition of knowledge building is to colonial extraction and exploitation.

Anyway… thank you if you made it this far!

Much love <3

— Hannah

References:

Check out this article from Agua Caliente’s website! https://www.aguacaliente.org/documents/OurStory-8.pdf

Balasse, Marie, Anne Tresset, Gaël Obein, Denis Fiorillo, Henri Gandois. 2019. “Seaweed-eating sheep and the adaptation of husbandry in Neolithic Orkney: new insights from Skara Brae.” Antiquity 93(370): 919-932. ff10.15184/aqy.2019.95ff. ffhal-02304703

Bibby, Bryan. 1996. The Fine Art of California Indian Basketry. Crocker Art Museum. Sacremento, CA. ISBN 0-930588-87-8.

Bryne, Stephen, Devlin Gandy, David Wayne Robinson, and John Johnson. 2016."A Recently Discovered Cache Cave in the Backcountry of Santa Barbara County, California." SCA Proceedings. 213-223.

Harris, L Stuart. 2021. “Skara Brae curbstone decipherment.” Link

Sakai, M., A. Sakurai, S. Lu, J. Olano, C.M. Albrecht, H.F. Hamann, M. Freitag. 2024. “AI-accelerated Nazca survey nearly doubles the number of known figurative geoglyphs and sheds light on their purpose.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121 (40) e2407652121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2407652121.

Stieglitz, Robert R. 1994. “The Minoan Origin of Tyrian Purple.” The Biblical Archaeologist 57(1): 46–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/3210395.

Hearst Museum Portal. 2024. “Presentation Basket.” ark:/21549/hm21010022478. https://portal.hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu/catalog/50fa07f1-37ba-4dce-87fe-b48937d1715a

This is all so fascinating! I plan to read more about it. I know you said the Nazca lines are very much human but it's funny because the 2nd new image seems so much like an alien and a spaceship 🤣 I wish I could see them but I'm terribly afraid of heights

As someone who’s seen the Nazca lines, it was so cool to see them mentioned. Excellent article!